Witness Stone Project Overview

The Witness Stones Project is a non-profit community initiative whose mission is to restore the history and honor the humanity of the enslaved individuals who helped build our communities.

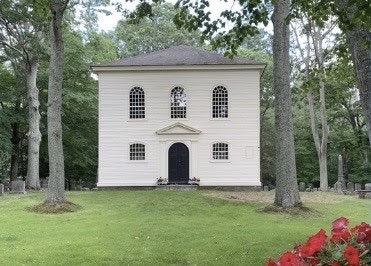

Trinity Church was founded in 1771 by Godfrey Malbone, a slave owner whose family fortune was made in the slave trade. Malbone’s original building, Old Trinity, is the oldest Episcopal church in the state and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

For the past year, parishioners of Trinity Church have worked with representatives of The Witness Stones Project to learn the history of Connecticut’s participation in the slave trade and its unjust system. With these Witness Stones (the first two subjects of our research), we begin to bring to light the stories of the enslaved people who built this historic house of worship, many of whom are buried nameless in the churchyard. Our first Witness Stones were installed on June 15, 2025 in honor of two slaves of the Malbone estate known simply as Jenny and Sias.

The Research Summary

Although it may be difficult for us to accept, it is unarguable that this parish that we love grew directly out of the institution of chattel slavery. The fortune that established Old Trinity was made by trafficking in human lives; enslaved people constructed this beautiful building where our parish story began. Nor are these founding conditions unusual – at its height in the 1800s, the slave trade out of Newport was a major economic force that shaped this region. The names and stories of most of the enslaved who helped eastern Connecticut to prosper are lost to us, but we owe them a great deal.

The Malbone Family, Jenny, and Sias

The man directly responsible for Old Trinity’s birth, Godfrey Malbone Jr., was the son of one of the richest men in the Colonies. Godfrey Malbone Sr. of Newport had amassed his wealth as a merchant, privateer, and slaver during the early decades of the 1800s. The elder Malbone’s holdings at the peak of his career were vast; his many properties included 3,100 acres of prime land in Pomfret (now Brooklyn), tended (as some histories attest) by 50 or 60 enslaved people. Malbone family lore maintains those enslaved people had helped ward off pirates attacking the ship that carried them, and Malbone rewarded them with servitude in Pomfret, rather than on the Caribbean sugar plantations. Malbone suffered a series of misfortunes in the mid-1700s, however, and his wealth began to dwindle. By 1745 he was forced to recall Godfrey Jr. from England (where he was attending Oxford University) to help with the family business. By 1764, Malbone Sr. was bankrupt. He quitclaimed the Pomfret land and 27 enslaved people to Godfrey Jr. and his younger son John, tasking them with selling off assets to cover his debts.

In 1766, a massive fire burned the Malbone mansion in Newport to the ground. Godfrey Jr. and his wife Catherine moved into a simple farmhouse on the Pomfret acreage. We don’t know how they viewed their straitened circumstances. Both were born to great privilege; it is likely that neither had the skill to manage a farm or even a rustic household. They had no children to share the workload, and Catherine’s health was fragile. The 27 enslaved people listed on the deed (perhaps joined by others from the Newport household) were undoubtedly responsible for the Malbones’ upkeep. Listed among them was a woman named Jenny and a boy named Sias. Jenny could have been as young as 15 or 16 and still be considered a woman, but could as well have been older. Sias would have been old enough to work (anywhere from 5 to 6 to a young teen), but was not yet at full adult capacity. It is quite possible that both Jenny and Sias were born on the Pomfret plantation. It is also possible that Jenny was among the group that defended the Malbone ship against the pirates – but again, we have no way of knowing.

Old Trinity is Built

The Malbones settled into their quiet homestead, Godfrey seemingly content with his new role as a landed gentleman, except that he was unable to practice his Anglican faith. The nearest Anglican church was in Norwich, some 25 miles away. In the New England colonies, the Congregational Church was effectively the state church. Anglicanism was viewed with suspicion, particularly as relations with England soured in the years prior to the Revolution. Malbone, when required to pay taxes toward the construction of a new Congregational church, circumvented the regulations by committing to build his own church. It was a decision that cost him much of his remaining fortune, but Malbone seems to have been a devoted Anglican. It must be acknowledged, though, that he was also a man of considerable temper who disliked being told what to do by those he considered his inferiors – most people! Some additional detail of the early church appears in Sketches of Church Life in Colonial Connecticut written in 1902 Being the Story of the Transplanting of the Church of England into Forty Two Parishes of Connecticut, with the Assistance of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

Jenny, Sias & the Early Church

And who built this simple, but elegant structure? Malbone (for all his family had lost) was still one of the largest landowners in the region and he still owned the most slaves. The local farmers who were Anglican were not wealthy – their monetary contributions were modest, and few of them were slave owners. We must assume it was Malbone’s enslaved who built the church he designed. We have no record of how many people labored to create Old Trinity. We don’t know their names or what skills they brought to the project. Sias may have been among them; at the time the church was being constructed, he would have been of prime working age. If Jenny was involved, we must assume that it was in the form of domestic work behind the scenes.

The newly formed church maintained careful parish records from the onset. The enslaved were baptized (whether they wished it or not) and were expected to attend services seated up in the gallery. We have baptismal records for other Black people, but none for Jenny or Sias. Were they baptized earlier elsewhere?

Sias next appears in 1775 in a fugitive slave notice, escaped from Malbone. He is described in detail: He is about 25, healthy (“lusty”) and New England born (supporting the notion that he may have been born here on Malbone’s land). He is “active, bold, and impudent” – in other words, no more inclined to submit to authority than Malbone himself. His clothing includes a “smartly cocked hat,” and the reward posted for him indicates that he had value. We assume that he was returned to Godfrey’s household to wait for another opportunity for freedom.

As the Revolution ground on, the Malbone fortune diminished further. Loyalist assets were seized. Trinity was shuttered and the Rev. Daniel Fogg, the parish’s second priest and first rector, conducted services in the Malbone household, where he had been housed since his installation. A 1779 letter from Godfrey to his brother John in Newport gives the sense of a man fighting for every scrap, keenly aware of how far he has fallen. He refers to himself in rather ironic terms as “the Squire.” He enumerates the household as consisting of 12 people: he and his wife, the Rev. Fogg, two nieces (presumably companions to Mrs. Malbone) and the “servants,” of whom only 7 remain. The rest are “dispersed.” Jenny has recently died, and Malbone refers to her with affection and admiration as “poor excellent Creature.” He goes on to say that “Master Sias” (who had evidently been sold in the intervening time to John Dorrance of Voluntown) had escaped from there as well. That fugitive notice described him as being “addicted to swearing.” And there Sias disappears.

These brief glimpses are all we have of Sias and Jenny. There is much here to make us wonder. What was Jenny to Malbone that her death caused him such regret? Was she a compassionate nurse to his wife? Was it her skill that held the household together? Did the two young gentlewomen from Newport learn practical skills from her? Why is there no burial record for her in the parish register? And Sias – did he give Malbone as good as he got? His strong spirit and determination practically leap out at one even from these brief historical records.

Malbone died at age 64, certainly not destitute but far from the fabulous wealth of his early life. In that letter to his brother, one gets a sense that his reversal of fortune may have helped awaken him to the humanity of those he enslaved, and to his own dependence on their service.